Summer hiring likely to be challenged by a tight labor market

Normally during this time of year, restaurants across the country would be staffing up for the opening weekend of the summer season. These summer jobs are typically filled by a wide variety of individuals – teenagers, college students, teachers – even retirees who want to pick up a few shifts at the 19th hole of their local golf course.

Given the current labor market environment, restaurants will likely need maximum participation from all of these groups if they want to fill their open vacancies for the summer season.

While the restaurant industry is expected to expand payrolls this summer, it will likely be a mix of both pandemic recovery and seasonal jobs. Many restaurants are still well below normal staffing levels and are working to rebuild their teams back to pre-pandemic levels. Others are seasonal restaurants that do the bulk of their business during the summer months and need to staff up to handle the influx of travelers and tourists.

This article examines some of the factors that will impact restaurant staffing levels during the 2022 summer season.

A summer employment juggernaut

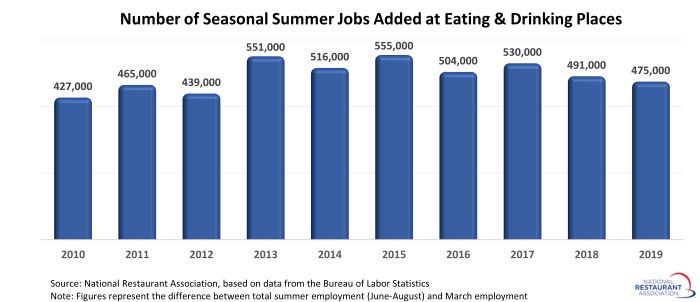

The restaurant industry is typically the nation’s second largest creator of seasonal jobs during the summer months – ranking only behind the construction industry. In the five years prior to the pandemic (2015-2019), eating and drinking places* added an average of 511,000 jobs during the summer season.

On average during the 2015 – 2019 period, the states that added the most eating and drinking place jobs during the summer seasons were New York (41,000), California (35,400), Massachusetts (28,600), New Jersey (25,800), Texas (24,400), Illinois (22,200), Ohio (18,200), Michigan (17,700), Maryland (15,200) and North Carolina (15,200).

The states that registered the largest proportional employment increases during the 2015 – 2019 summer seasons were Maine (30%), Alaska (20%), Delaware (17%) and Rhode Island (15%).

View the historical summer employment data for every state.

Job openings near record high

Even before most restaurant operators started interviewing for summer jobs, the help wanted signs were out in full force. Many of these positions went unfilled, as job openings rose sharply in recent months.

The restaurants-and-accommodations sector** had nearly 1.5 million job openings on the last business day of March 2022, according to Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). While this was down somewhat from the record 1.8 million unfilled job openings recorded in December 2021, it was nearly double the typical readings during the months leading up to the pandemic.

March also represented the 12th consecutive month with at least 1 million unfilled job openings. Prior to this 12-month streak, hospitality sector job openings had only surpassed 1 million once during the entirety of the JOLTS data series which dates back to 2000.

Restaurant operators confirm that the labor pool is very shallow. In the Association’s May 2022 tracking survey, 58% of operators said recruiting and retaining employees is the top challenge currently facing their business.

Note: The job openings data presented above are for the broadly-defined Accommodations and Food Services sector (NAICS 72), because the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not report data for restaurants alone. Eating and drinking places account for nearly 90% of jobs in the combined sector.

Competition for talent is running hot

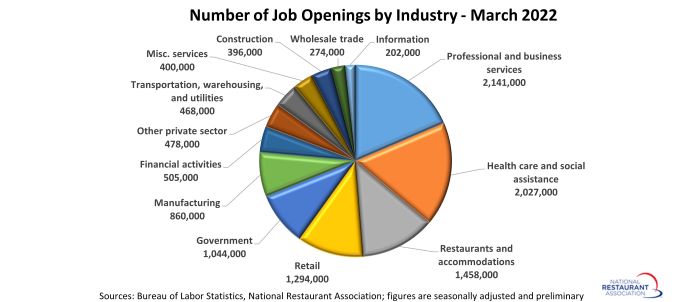

It is not only restaurants that are trying to attract employees. Five different industry categories had more than 1 million unfilled job openings in March. This group was led by the professional and business services and health care and social assistance sectors, which each had more than 2 million vacancies.

Retailers – who often compete with restaurants for employees – reported 1.3 million job openings in March.

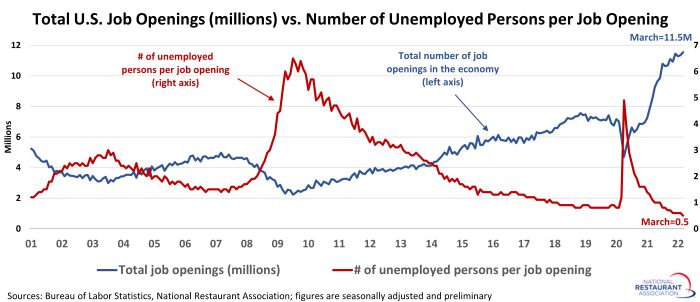

In total, there were 11.5 million job openings in the U.S. economy in March 2022 – the highest level on record. This was 4.5 million (or 65%) more openings than the economy had in February 2020 before the pandemic.

At the same time, the number of unemployed people available to fill these positions trended steadily lower. As of March 2022, there were only 0.5 unemployed persons per job opening – the lowest level on record. Put another way, there were 2 job openings for every person that was officially categorized as unemployed (which is defined as individuals who are currently not working and are actively looking for a job).

In comparison, during the peak of the Great Recession in 2009, there were more than 6 unemployed persons for every job opening in the U.S. By these measures, the economy is clearly experiencing the tightest labor market since the beginning of this BLS data series in late-2000.

Youth movement

With that as a backdrop, employers must look beyond the unemployed to fill vacancies. Instead, they will need to draw new people into the labor force to meet their summer staffing needs.

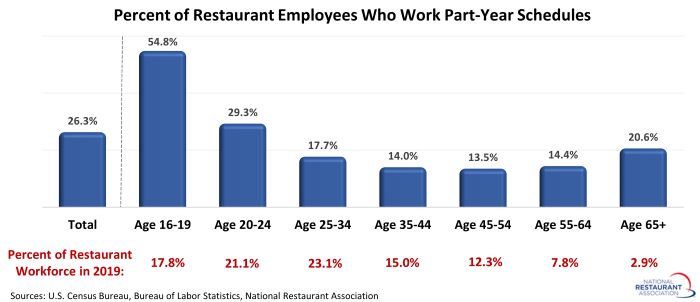

When it comes to finding a cohort that is predisposed to working a seasonal job, teenagers are the first place to start. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau, 55% of teenage restaurant employees work part-year schedules. That's more than double the 26% of all restaurant employees who only work for part of the year.

Young adults also have a higher rate of seasonal employment than the overall industry workforce: 29% of 20-to-24-year-old restaurant employees work part-year schedules.

Taken together, these two age cohorts represented nearly 4 in 10 restaurant employees in 2019 before the pandemic.

Teens are getting back to work

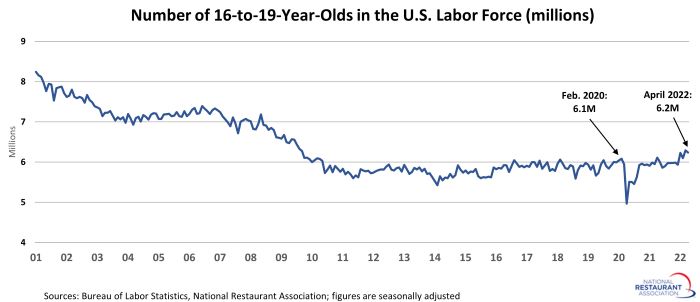

For employers looking to fill positions, a positive development is the rising number of teenagers entering the workforce. According to BLS data, there were over 100,000 more teenagers in the labor force in April 2022 than there were in February 2020 before the pandemic began.

This also represented the highest number of teenagers in the labor force since 2009. Although the size of the teenage workforce will likely never return to its all-time highs – there were more than 9 million teenagers in the labor force during the late-1970s and early-1980s – the recent upward trend is good news for sectors that rely on younger workers.

Prior to the pandemic, restaurants were the largest employer of teenagers, providing job opportunities for 1.7 million 16-to-19-year-olds (or 34% of all working teens).

The trends are not as positive for the next rung up the demographic ladder, as the number of young adults in the labor force has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. According to BLS data, there were 600,000 fewer 20-to-24-year-olds in the labor force in April 2022 than there were in February 2020.

In terms of pre-pandemic comparisons, the 14.7 million 20-to-24-year-olds in the labor force is the lowest reading since 2002.

A path forward

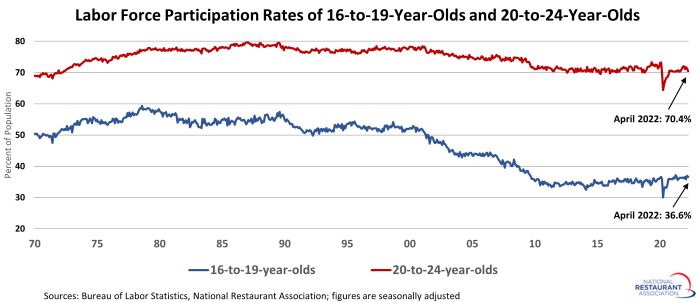

Just because there are about a half million fewer 16-to-24-year-olds in the labor force now than there were before the pandemic, it doesn’t mean this cohort should be written off. Labor force participation rates remain well below historical levels, which suggests there is still potential for growth.

In April 2022, only 36.6% of teenagers participated in the labor force. This was down from over 52% at the turn of the century – and was well below the record high of nearly 60% in 1978. At current population levels, if this cohort’s labor force participation rate would rise to 40%, it would mean an additional 600,000 teenagers in the workforce.

Labor force participation rates are also dampened for young adults. The current 70.4% participation rate of 20-to-24-year-olds is nearly 10 percentage points below the record highs reached in the mid-1980s. If this increased to 73%, it would add more than 500,000 young adults to the labor pool.

If employers can successfully incentivize teenagers and young adults to get off the sidelines and into the workforce this summer, the goal of a fully staffed restaurant may be achievable.

*Eating and drinking places are the primary component of the total restaurant and foodservice industry, which prior to the coronavirus outbreak employed 12 million out of the total restaurant and foodservice workforce of 15.6 million.

**The job openings data presented above are for the broadly-defined Accommodations and Food Services sector (NAICS 72), because the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not report data for restaurants alone. Eating and drinking places account for nearly 90% of jobs in the combined sector.

Read more analysis and commentary from the Association's chief economist Bruce Grindy.